Hello there,

What are you betting on for the next 5-10 years?

The first time a friend asked me this question, I was dumbfounded. At the time, I managed to cobble a response but more importantly that question stuck. In hindsight, the better answer would have been “I’m not sure.”

Every choice is a bet. Meaning in life, we are juxtaposed to place bets whether knowingly or unknowingly. Jobs and relocation decisions are bets. Sales negotiations and contracts are bets. Buying a house is a bet. Ordering chicken over steak is a bet. Starting a company is a bet. Netflix and chill is a bet.

For instance, by choosing an art degree over a science degree, I made a bet (at the time unknowingly), on the latitude of general skills over technical skills to propel my career. Whether it was the best decision, the verdict is still out. ?

The question is very good in the sense that it pushes us to frame our deliberate choices instead of frantically leaving our life to chance or natural progression choices alone.

A bet is the fillable gap behind Peter Drucker’s, “you can’t manage, what you don’t measure” and the preamble to decentralized thinking in thinking big.

By nature of calling it a bet, we are primed into thinking of the risks, incentives, analytical approaches that inform our positions and probabilistically thinking in an uncertain world.

Here we go!!

Thinking in Bets

Every day in our lives, whether in our careers, education, social relationships, we make countless decisions, under conditions of uncertainty. Within these decisions, there are layers of bets that reveal our option strategy in life.

Most of these decisions are not a bet against another person, writes Annie Durke in Thinking in Bets, rather a bet on our future versions of ourselves that we are not choosing. At stake is that the return to us (happiness, money, time, health) will be greater than what we are giving up by betting against alternative futures.

In her book, she compares life to poker, as opposed to chess. Poker like life is attuned to life’s information asymmetry where decision making involve luck, uncertainty, risk, and occasional deception.

If there weren’t luck involved, I would win every time – Phil Hellmuth, Fifteen-time World Series of Poker winner

In Chess, there is no hidden information and very little luck. The winner is usually the one with the better moves.

Trouble with thinking like a chess player lies in the concept of resulting, which is the tendency to equate the quality of a decision with the quality of its outcome. This is a risky and incorrect thing to do with any decision that has a probabilistic outcome.

When I consult with executives, I sometimes start with this exercise. I ask group members to come to our first meeting with a brief description of their best and worst decisions of the previous year. I have yet to come across someone who doesn’t identify their best and worst results rather than their best and worst decisions – Annie Duke.

Good decisions increases the chance of a good outcome but doesn’t guarantee it. You could make the best possible play at every point in the game and still lose. Similarly, you could make the worst plays and still win. This is a lesson that professionals in probabilistic domains such as poker and venture capital tend to grasp more often than others.

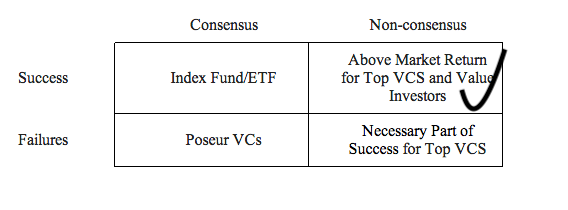

For instance, Marc Andreessen, suggests a two-by-two matrix to evaluate potential venture capital investment that optimizes for placing bests on the right and non-consensus axis. Why? Venture capital, more so like many anti-fragile careers, follows a Power Law Distribution.

A chess playing VC is inclined to follow the crowd reclining them to the dossier of Poseur VCs who never make up for the wrong bets since they don’t optimize for the home runs.

Learning to distinguish the difference between results and decisions is what thinking in bets is all about. Decisions are bets on the future. They aren’t “right” or “wrong” based on whether they turn out well or not.

This specific mindset teaches us that success is not only a measure of effort or skill but is also very much a component of the quality of decision making (bets) and luck. Being wrong becomes subject to a wider sample of causal factors.

On the other hand, we are probabilistically less likely to fall in love with bets compared to beliefs. Beliefs work towards giving us a narrative of our life story and being wrong doesn’t fit that narrative. Bets vet our beliefs and check our decisions through the skin in the game filter.

It was not enough for Jeff Bezos to believe in the World Wide Web alone, he had to quit his job at D. E. Shaw in the middle of the year, foregoing a yearly bonus to start Amazon.

It was not enough for him to believe in the information revolution alone, but he also had to decide that books would be his beachhead. (Bet).

It was out of his bet paying off that led to Amazon being valued at billions of dollars and consequently fulfilling his regret minimization framework.

When we are challenged to demonstrate skin in the game – bet money, time, reputation – on a belief we are much more likely to:

- Examine our information in a less biased and more objective way.

- Be more honest with ourselves about how sure we are of beliefs.

- Be more open to updating and calibrating our beliefs.

The players who win bets in the long run are the one’s whose beliefs and bets are attuned to life’s game with some sprinkles of luck.

Best Stuff I Read

2. Common Causes of Very Bad Decisions

Italian psychologist Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini was once asked why people keep making the same mistakes.

He said:

Inattention, distraction, lack of interest, poor preparation, genuine stupidity, timidity, braggadocio, emotional imbalance, ideological, racial, social or chauvinistic prejudices, and aggressive or prevaricatory instincts.

Morgan Housel, one of my favourite internet writers, further adds:

- Incentives can tempt good people to push the boundaries farther than they’d ever imagine.

- Tribal instincts reduce the ability to challenge bad ideas because no one wants to get kicked out of the tribe.

- Ignoring or underestimating the full range of potential consequences, especially tail events that seem rare but have catastrophic effects.

- Lots of little errors compound into something huge.

- An innocent denial of your own flaws, caused by the ability to justify your mistakes in your own head in a way you can’t do for others.

- Probability is hard. Black-and-white outcomes are more intuitive.

- Underestimating the need for room for error, not just financially but mentally.

- Underestimating adaptation, both present and future, leaving you convinced that history will repeat itself and bitter when it doesn’t.

- Being influenced by the actions of people who are playing a different game than you are.

- An inability to know how you’ll respond to stress causes you to take risks you think you can handle but you’ll actually regret when they turn on you.

- Too much extrapolation of past successes leads to overconfidence, stubbornness, and a narrow view of future risks.

- Wrongly assuming that the information you have at your disposal tells a complete picture of what you’re dealing with.

- Misreading the cause of others’ successes or failures in a way that tempts you to overemphasize parts of their strategy when attempting to copy what they did.

What I’m Watching

A Coach’s Rules for Life puts the spotlight on coaches, and lets them talk about themselves, their motivational methods and philosophies about life and sports.

If you’re enjoying the Bits by Muigai newsletter, I’d love it if you shared it with a friend or two. You can send them here to sign up and get a feel the past editions.

Always feel free to shoot me an email at muigai@solomonmuigai.com with questions, critiques, half-formed ideas with a need of jack to bring to life or just to say hey.

Until next Saturday, have a happy weekend.

Solomon Muigai.