It is amazing how little information we needed as kids to make a decision on who we wanted to be when we grew up. We didn’t need to get embroiled in the “back end” when we fell in love with the “front end.” Most of our career choices were as a result of peer mimicry, family preference, something we saw on TV or a random pick from our school textbooks.

Growing up, we quickly realize opportunities are scarce and focus on the low hanging fruits. Granted, we chose what’s available to first get our heads inside the game then we can navigate to our passion. But again, we continue to assess work based on the “front end” albeit a little bit more advanced. It’s no longer just about the fascination but also about the availability, salary, job title, job description, and the boss.

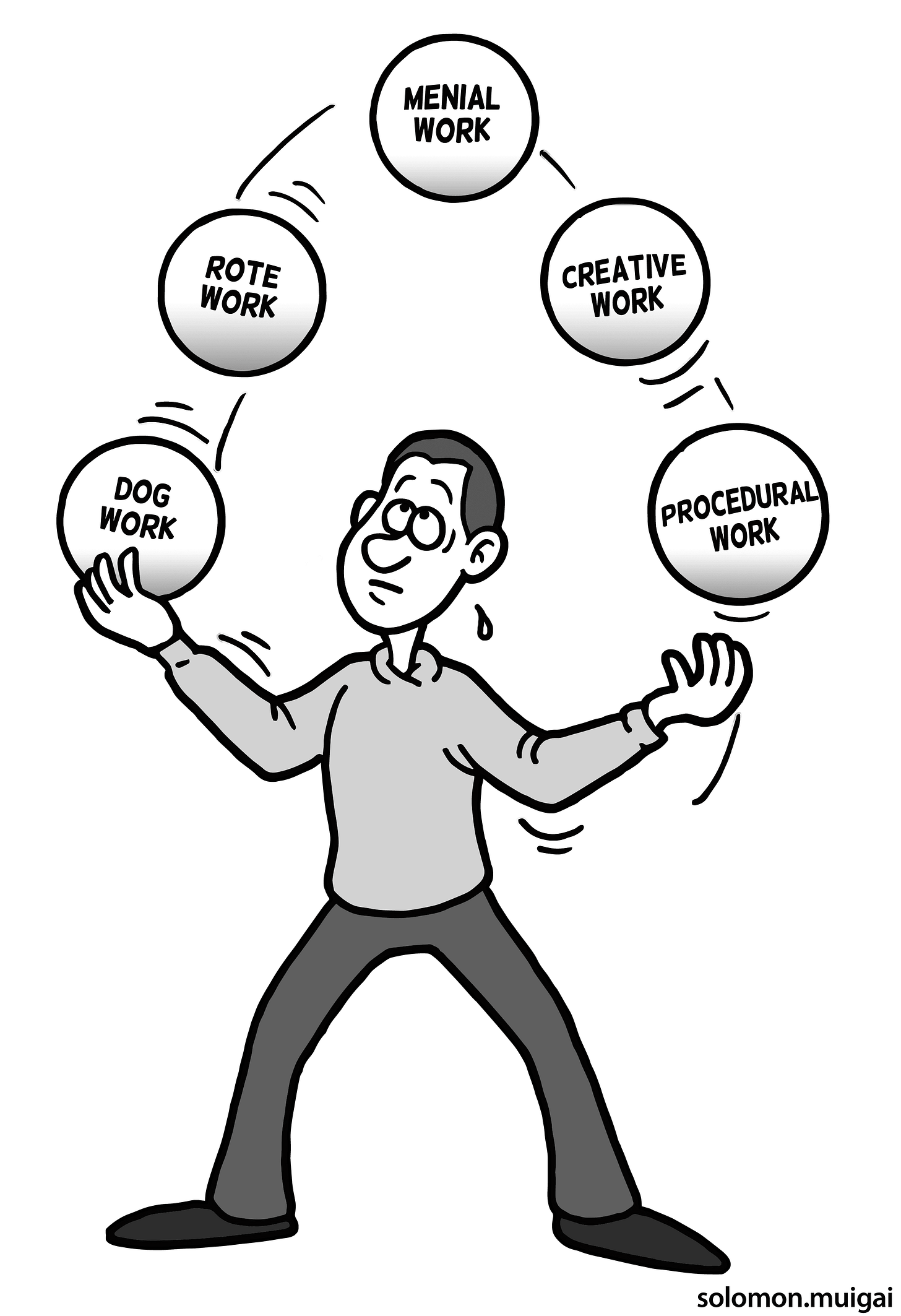

If we were to look behind the scenes, we would find every worker tossing, juggling and trying to balance different work components on a day to day basis.

Every job is a sum of all these work components – it’s just that they are not all equally distributed. The variance is a result of factors such as seniority, industry, profession, company stage, personal preference (knowingly or unknowingly) among other things.

I believe work falls under two broad categories: Menial Work and Creative Work. Menial work is what society has already defined for us. It comes by default since we operate in a shared world with systems, processes, and laws. Creative work, on the other hand, is about forging our identity. It is a product of our imagination. A way in which we can leave our footprint in a world not least traveled.

Comparative Advantage = high creative to menial ratio.

Net Productivity = creative work – menial work.

Average = high menial to creative ratio.

Ratio is Kinetic

Jobs at the very core are about adaptation. An oscillation between the M:C ratio based on the stage of our careers, the needs of our company and megatrends in our industry. The unspoken rule is that we should be able to perform any task when needed. Nothing is not our job.

A lot of unhappiness in the workplace is a result of the ratio not coinciding with our expectations. We are at our happiest when we feel our contribution is unique and useful to our organization. Not when the bulk of our work revolves around following a well-defined path complete with signages.

In a world where job adaptability is glorified, problems are solved as they come along, money acts as an end to a means and mimicry is the norm, the ratio is construed to be highly asymmetrical. Our current M:C ratio is always a by-product of the evolving nature of problems present at any one given time in our work environments. One day we are brainstorming over high-quality problems. The next day we are trying to figure out how the copier works.

The nature of problems in our noosphere is heavily influenced by our work environments. A noosphere convoluted with mundane problems results in averageness. Conversely, a noosphere convoluted with high-quality problems results in a higher success probability.

The sweet spot is finding a delicate balance, without veering too far off the “good at both” quadrant. If we find ourselves in jobs, that utilize little of our creativity, our after office hours are crucial to reducing the disequilibrium. If we find ourselves in highly creative roles, we should not forget that it is through menial work that rails are created to complete the cycle of creativity.

To be a billionaire you must have a stomach for meetings with regulators, lawyers, and public appearances. To ascend in a corporate hierarchy, you must perform a slew of low-value procedural tasks handed to you. To succeed as a junior, you need to have the humility to handle the dog work thrown your way. To build your business from the ground up, you need to put on a hard hat, throw some work boots on and get right into the weeds. To understand a business bottom-up, you need to get to the ground and experience pain points as if they were your own.

Mental Energy is Finite But Replenishing

Our productivity is based on our ability to build greater energy capacity. To build greater capacity, we must be able to distribute our 96 energy blocks (1 hr = 4 energy blocks) in a day in the most effective way possible.

We operate in a work environment governed by the industrial chronological system of the 9 to 5. Keyword is “industrial.” This is a system built for machines. Not for us. According to chronobiology, our bodies are built for sprints followed by periods of rest in what is known as the Ultradian Rhythm. These are biological rhythms that break down our days into sizeable recurrent chunks of alternating periods of rest and activity. Naturally, we experience 90 minutes of activity followed by 20 minutes of rest cycled over and over throughout a day.

Not all 90/20 time blocks are equal. With fatigue as the leading cause of this inequality. It is on the same breadth, that we would expect to get more value from a $100 haircut than a $5 one, that we would aim to get creative work done on a high energy block than on a low energy block.

This is why time blocking combined with the Pomodoro technique is such an effective productivity technique. It allows us to be in sync with our natural energy rhythm without leaving us at odds with our energy capacity. There is value in knowing objectively when we are good to tackle our most cognitively demanding tasks and when the only thing we are good for is watching Netflix.

Having a daily to-do-list as a primary productivity organization system shouts that we do not have control over our schedule but trust in our ability to get all the work done by the end of the day. That is fine – but often what tends to happen is we subconsciously lose track of efficiency. We fall into victims of Parkinson’s Law which states that work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion. We end up doing more with what can be done with less.

Higher internal efficiency is repeated action enhanced through batching of tasks that operate on a similar energy frequency. The secret lies in allowing for the least cognitive switch between the M:C to reap the benefits of the other. In other words, it is infinitely easier to unstick ourselves from one menial task to another. Rather from a menial task to a creative task. This speeds the leeway through which our basal ganglia trivializes, automates and dumps tasks into our “no-brainer” category.

What we do with the extra brainpower is the biggest differentiator of the success levels in our careers. Average people will sit on the 10 perfect reps of the same weight for weeks – even months. Then there are those who will always aim for that one-rep max every single week.

One thing we must come to terms with is that net energy never never finds a home. It is either sub-consumed by other people’s demands – both socially and professionally. Or worse yet it exiles us to rest in motion. After all, our brains are wired to conserve energy.

Different Rules but Inter-dependable

The capacity to be creative lies within every human from birth. Yet creativity exists in disproportionate amounts in society. This asymmetry is an outcome of the nature of the creative process itself. Just like the wind not everyone can harness it.

If creativity is a process that allows us to extend our ideas beyond apparent limits prescribed by our society then there must be a form of transcendental inter-level movement of ideas. Nothing captures this process better than the Wallas four-stage model of the creative process.

- Preparation.

- Incubation.

- Illumination.

- Verification.

Curiosity naturally drives us to the preparation stage where we investigate a problem, need or desire in all directions. We read books, attend trainings, watch YouTube videos and subscribe to online courses. Through this immersion, we contemplate, form mental pictures, and incubate our ideas.

Often we put pressure on ourselves to process the ideas on-site through some concerted effort, but the bulk of high-quality ideas come with no direct effort exerted upon the problem at hand. This is largely because creativity is combinatorial. A remix of knowledge, bits of information, experiences, sparks of inspiration and other existing ideas that combine and recombine to morph into something “new.”

Temporary suspension of information processing allows us to maximize the upside of randomness and utilize the triggers in our external environment to solve problems that have been simmering at the back of our minds. It can take place on time spent either in conscious mental work on other problems – most likely solving menial problems- or through relaxation from work. This explains why some of our big ideas come to us in a wide-ranging prism from while in the shower, taking a walk or doing nothing.

It is counterproductive to start off our days with menial work for the simple reason that we won’t reap the benefits of the upside of performing menial work with a creative problem in mind. By starting with a creative problem, we open ourselves up to our external environment where lies the answers. We must always remember when our conscious brain is half asleep performing menial tasks, our subconscious is alert to solving the problems encountered in the creative process. One shot two kills.