Hi there,

Last week, we learned that for an artist to be successful in an outcome-based world, the art must speak industrial linguistic, and one way to do it is to through measurement.

This week we are looking into how measurement becomes a problematic solution for intuition through the “Goodhart’s Law” lens and possible solutions while in the conductor phase.

But first.

It’s incredible how measurement is such a crucial part of our lives. Everywhere you go, you are ranked.

School = grades. Job Hunt = ATS. Job = KPI. Content Marketing = SEO. Trust = Social Credit Score. Customer Satisfaction = Net Promoter Score.

People have gone to extra lengths to game measurements as there is general belief measurements and incentives are closely related. Here are a few examples that I came across.

In India, under the British Rule, the Colonial government was concerned about the number of venomous cobras in Delhi. The government thought it was a good idea to recruit the local populace in its efforts to reduce the number of snakes, and started offering a bounty for every dead cobra brought to its door. The unexpected result: People started to breed more snakes in order to get rewards. This is also referred to as the Cobra Effect — when an attempted solution to a problem makes the problem worse, as a type of unintended consequence.

In the 20th Century, Albert Einstein produced the world’s most famous equation, E=mc 2, which led to the atomic bomb and Allied victory in Japan and the end of World War II in 1945. What followed was a widespread belief in the academic world that quite frankly denotes why academics are academics. They deduced that “if Einstein’s one paper led to the atomic bomb that ended WWII, think what a thousand papers could do!” This birthed the “publish or perish” culture, with professors using the principle of the “least publishable unit”. Quantity rather than quality became the metric. That’s why John Ioannidis famously estimated 90% of medical research papers are false. This is why we hear today meat causes cancer and tomorrow that it is good for us.

These two examples point out what is wrong with measurement. All metrics of evaluation are bound to be abused.

Goodhart’s Law states that when a feature of the economy is picked as an indicator of the performance, then it inexorably ceases to function as that indicator because people start to game it.

But measurements are important nonetheless. Measurements are a tool that helps us get results. The danger is when you believe the simplified version is the full reality and not a simplification.

On the other side, one is also left to ponder of the illegible (hard to measure) – of what place is it in the outcome-based world?

Here we go!!

Illegible <> Legible

When translating intuition into measurement, it’s mindful to keep in mind Goodhart’s Law. But more importantly, it’s crucial we recognize not everything is measurable. There are domains where intuition flat out beats measurement.

Generally, there are three principles I keep in mind when thinking about the illegible:

1. There is value in the illegible if you know how to differentiate the legible from the illegible and distinguish their respective worth and limits.

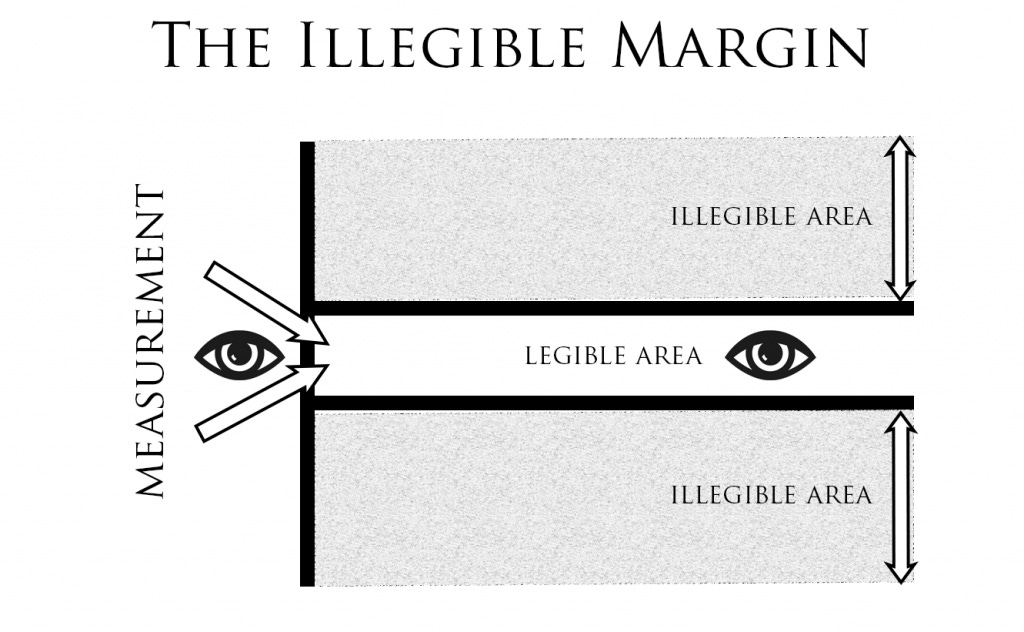

Finding a previously unseen margin (legible – illegible) is incredibly valuable. One way this can be seen is by reversing the usual order of thinking and or elimination.

Taylor Pearson gives a good example of the PC vs Mobile Usage Phase. One of the major reasons mobile usage overtook PC usage in the western markets was on the little pockets of time (margins), between meetings, or commuting, during the day which adds up to a lot.

Why do you think no other company capitalized on all the time margin that smartphone ecosystems have?

A core reason was that it was illegible, it was hard to measure. Who knew the collective five or fifteen-minute chunks of people’s days added up to so much?

Another brilliant real-life example is how Rory Sutherland, ended up moving into an apartment designed by Robert Adam, a Scottish neoclassical architect in the 1700s and one of the best of his era.

Generally, when people look for a house, they generally filter their dream house based on the legible through metrics such as location, price range, square footage…etc.

But remember, when measures become targets you miss the point.

Rory and his wife deliberately set out to invert the house-hunter’s decision tree by reversing the usual order of elimination. Instead of putting the legible first, they put architecture (illegible) at the top.

The Unexpected Result: A four-bedroom apartment on the roof of a Robert Adam house a mile outside the M25 that was barely more expensive than ordinary housing of similar size nearby.

2. Illegible ideas shouldn’t live in your head. Write them in a Decision-Making Journal. Raw intuition can be jolted down and measured by whether or not it achieves the end goal.

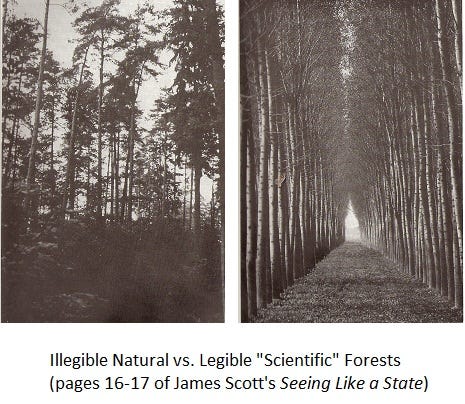

James Scott’s seminal work, Seeing Like a State introduced the concept of legibility through the rise of the modern nation-state in the 17th and 18th centuries where big data first came into the fold through census records.

High modernists, a term used by Scott to refer to the gatherers of big data, thought the rational way to organize something is with a geometric aesthetic. Aesthetics lead to simplification, and complexity as we know cannot be harnessed by simplicity. This is where failure starts.

The mistake we tend to make is that thriving, successful, and functional realities must necessarily be legible. They don’t. Illegibility has a function. For instance, illegible forests have a complex process that involves soil building, nutrient uptake, and symbiotic relationships between fungi, insects, mammals, and flora. A process that was not fully understood by the Germans in the late 18th Century. And a lesson they learned a century later.

While it’s increasingly hard to harness illegible ideas, it’s plausible to record them in a decision-making journal to help track the genesis of the thought process and outcome. This way we’re not fooled into thinking that we understand something we don’t and worst yet have no means to correct ourselves.

Here is a decision journal template by Farnam Street.

3. If you can make something legible, people will compete for it.

Finally, the obvious. The illegible is a competitive advantage. Something Warren Buffett tends to refer to as the moat. Keeping it a secret, makes it illegible to others and thus less likely to be replicated.

What better example than Coca-Cola, which makes us speculate even about its secret formula effect.

Cola, unlike other soft drinks, has no “taste memory” – the body doesn’t get sick of drinking it, and an addicted consumer can end up replacing their entire water intake.

Is this true? Your guess is as good as mine.✓

Best Stuff I Read

1. The Four Quadrants of Conformism

Paul Graham makes a very important draw board for classifying people based on their degree and aggressiveness of conformism. They are 4 kinds of people.

The aggressively conventional-minded ones, known as the tattletales. They believe not only that rules must be obeyed, but that those who disobey them must be punished.

The passively conventional-minded, aka the sheep. They’re careful to obey the rules, but when other kids break them, their impulse is to worry that those kids will be punished, not to ensure that they will.

The passively independent-minded, the dreamy ones. They don’t care much about rules and probably aren’t 100% sure what the rules even are.

The aggressively independent-minded, are the naughty ones. When they see a rule, their first impulse is to question it. Merely being told what to do makes them inclined to do the opposite.

There are more passive people than aggressive ones, and far more conventional-minded people than independent-minded ones. So the passively conventional-minded are the largest group, and the aggressively independent-minded the smallest.

—> Full Post.

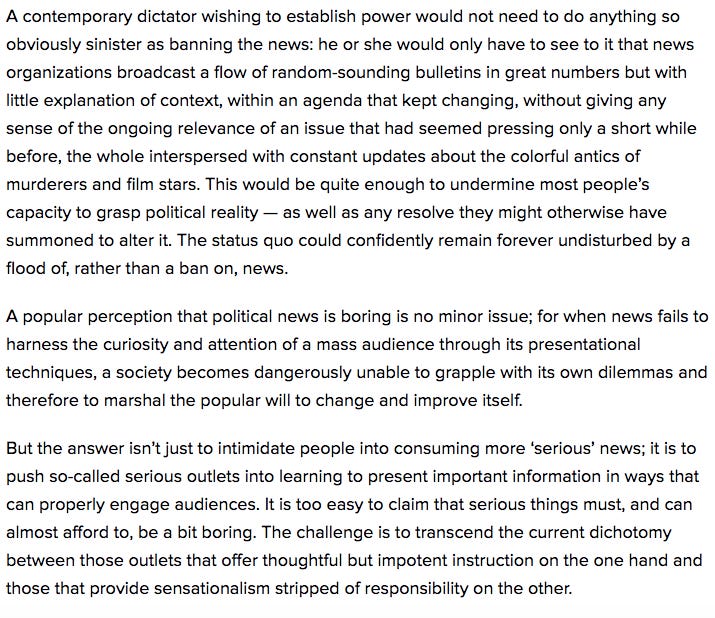

2. The Difficulties of Consuming News

What I’m Watching

April 6th, 1917. As a regiment assembles to wage war deep in enemy territory, two soldiers are assigned to race against time and deliver a message that will stop 1,600 men from walking straight into a deadly trap.

If you’re enjoying my Bits by Muigai newsletter, I’d love it if you shared it with a friend or two. You can send them here to sign up and get a feel of the past editions.

Always feel free to shoot me an email at (muigai@solomonmuigai.com) with questions, critiques, half-formed ideas in need of a jack to bring to life, or just to say hey.

Until next Saturday, have a happy weekend.

Solomon Muigai.